GIOS M10: Synchronization Constructs

Module 10 of CS 6200 - Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems @ Georgia Tech.

More Synchronization Constructs

Synchronization involves coordinating access to shared resources across concurrently-running processes. We’ve already discussed synchronization in previous lessons, though - what more is there to add?

Spinlocks

A Spinlock is a low-level synchronization construct supported by the operating system. Spinlocks are very similar to mutexes in that they provide mutual exclusion based on a locking mechanism.

1

2

3

spinlock_lock(s);

// critical section

spinlock_unlock(s);

However, spinlocks do not block on a failed mutex attempt. Instead, they spin - repeatedly check to see if the lock is free - until successfully acquiring the lock.

Semaphores

Semaphores are another synchronization construct representing a generalization of mutexes. In the case of a mutex, we have binary locking - a task may only acquire the mutex if it is unlocked (1) as opposed to locked (0). Semaphores offer a similar locking structure, but depending on some maximum number of accesses $N$. More specifically…

- Semaphore counter is initialized with some maximum value, representing number of concurrent threads / processes which may access shared resource.

- On every successful lock attempt by a task, semaphore counter is decremented by one.

- In the case where the semaphore counter is zero, an inbound task cannot access the shared resource.

- Once a task is finished with the resource, it “exits” the semaphore by incrementing its counter.

A mutex is therefore functionally equivalent to a semaphore with maximum value of one, although semaphores do not have the concept of “ownership” defined by a mutex.

Reader/Writer Locks

We are typically interested in mutual exclusion within the context of two possible scenarios:

- Reader: concurrent access to resource is permitted, since tasks do not modify the resource.

- Writer: only a single task should access the resource at a time, to ensure any updates are not overwritten by another task.

linux/spinlock.h provides Reader/Writer Locks to directly support this functionality.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

#include <linux/spinlock.h>

rwlock_t m;

read_lock(m);

// critical section

read_unlock(m);

write_lock(m);

// critical section

write_unlock(m);

User-defined programs implementing lower-level synchronization constructs (e.g., mutexes, semaphores) can accomplish the same functionality as reader/writer locks. Reader/writer locks simply provide an abstraction to facilitate easier usage / implementation.

Monitors

Monitors are an even higher-level synchronization construct which oversee all aspects of shared resource access. For example, when using a monitor to regulate shared resource access…

- On Monitor Entry $\rightarrow$ all necessary read vs. write / acquire lock operations are performed by the monitor.

- On Monitor Exit $\rightarrow$ all necessary unlock / free operations are performed by the monitor.

Signaling operations involving condition variables are typically still the responsibility of the user.

Others

There are also many other synchronization constructs which we won’t discuss in this course!

Spinlocks: Hardware Support

Spinlocks are one of the most basic synchronization primitives. For this reason, hardware has been explicitly designed to directly support and improve the efficiency of spinlock operations. In this section, we will follow The Performance of Spinlock Alternatives for Shared Memory Multiprocessors to better understand integration between hardware and spinlock mechanisms.

What’s the Purpose of Hardware Support?

Consider the following example of a purely code-based spinlock implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

def spinlock_init(lock):

lock = free;

def spinlock_lock(lock):

while (lock == busy):

spin();

lock = busy;

def spinlock_unlock(lock):

lock = free;

During the call to spinlock_lock, multiple tasks may exit the while loop simultaneously when a lock becomes free. Each of these tasks may then proceed to acquire the lock, which is not consistent with a correct implementation of mutual exclusion.

Therefore, we must have some mechanism where lock checking and acquisition are an atomic (indivisible) operation. This would effectively guarantee that only a single task can acquire the lock at a time. To make this work, we must rely on hardware-supported atomic instructions.

Atomic Instructions

Different hardware architectures offer different support for Atomic Instructions, which are operations guaranteed to complete in an all-or-none fashion (even if the operations are sequential in nature).

In the context of spinlocks, we would like to have an atomic test_and_set instruction:

- Test $\rightarrow$ tests original lock status.

- Set $\rightarrow$ updates lock status to busy once acquired.

Since atomic instructions are hardware-specific, we must ensure software is properly ported to function across different operating systems.

Review of Shared Memory Multiprocessors

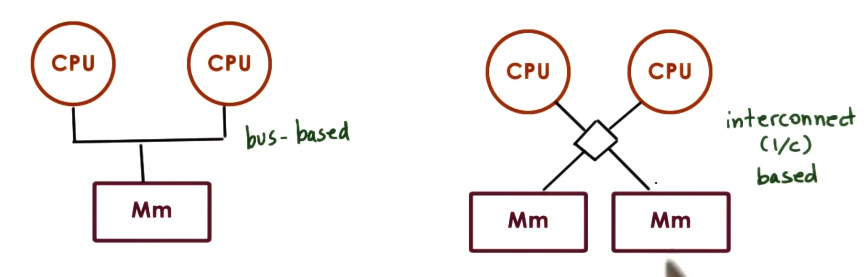

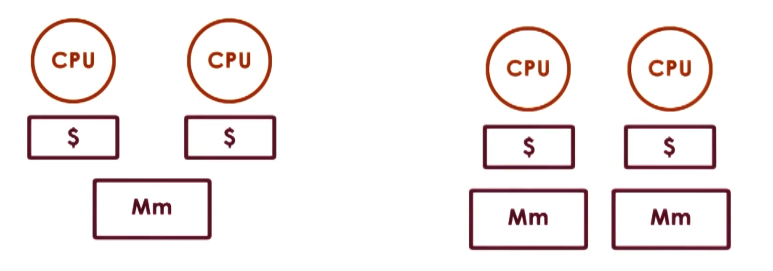

Recall that a Shared Memory Multiprocessor (SMP) consists of multiple CPUs, and some shared memory region which is accessible across CPUs. There may be one or many shared memory components.

In addition to shared memory, each CPU has its own cache to hide latency associated with frequent memory access. Memory latency is even more of an issue on shared systems due to contention with the shared memory component; therefore, caching is particularly useful for speeding up memory access operations.

What happens in the case when the CPU writes to memory, but some outdated value is still present in the cache? This is even more of an issue when multiple different CPUs have access to the same memory! Cache Coherence refers to a class of mechanisms for ensuring memory updates are propagated through all relevant caches. These mechanisms include…

- Write-Invalidate (WI): if one CPU updates a memory location, the hardware invalidates this memory location for all other caches.

- Benefit: lower bandwidth + amortized cost (bus / interconnect does not need to transmit data to all possible caches).

- Write-Update (WU): if one CPU updates a memory location, the hardware ensures all other caches referencing this memory location are updated.

- Benefit: data is available immediately on all caches. Outweighs cost in the case where the memory location is frequently utilized across CPUs (i.e., frequent cache hits).

Cache coherence requires special consideration in the context of atomic instructions. For example, if we have two CPUs each attempting to perform an atomic instruction regarding memory location $X$, what happens when each CPU performs the atomic to update its own cached version of $X$? For this reason, atomic instructions always bypass the cache and directly access the shared memory component. This serves to provide a uniform entry point where all atomic instructions can be organized and sequentially arranged.

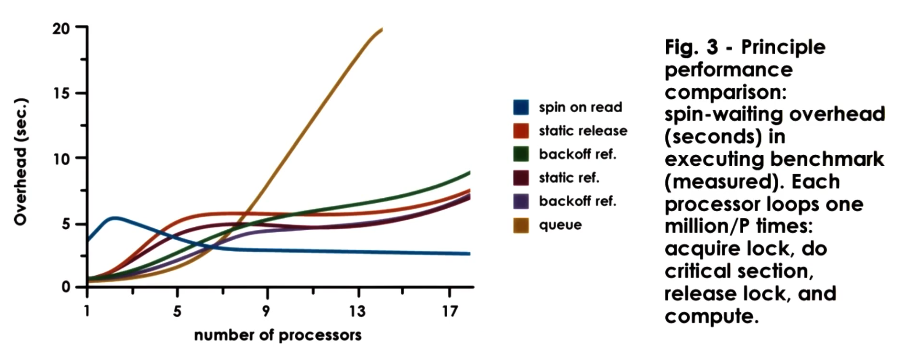

Spinlock Performance Metrics

What performance metrics should we consider when evaluating different implementations of spinlocks?

- Latency: time to acquire a lock when it’s free.

- Delay: time to stop spinning and switch to acquiring the lock.

- Contention: time lost due to bus/network interconnect traffic in SMP system. Contention is a function of both direct memory accesses and cache coherence mechanisms.

Our goal is to minimize each of these values. Note that this implies certain conflicts; minimizing latency and delay work against minimizing contention.

Spinlock Implementations

The Test-and-Set Spinlock (discussed earlier) involves an atomic instruction which checks and updates lock status to acquire a lock. The atomicity of the test_and_set instruction implies minimal latency. Additionally, delay is low due to the while loop - we are continuously issuing the test_and_set instruction to check and update the lock. This causes issue with contention, since each task (on each CPU) is constantly using the bus / interconnect to write lock status to shared memory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

def spinlock_init(lock):

lock = free; ## 0: free, 1: busy

def spinlock_lock(lock): ## spin

while(test_and_set(lock) == busy):

continue

def spinlock_unlock(lock):

lock = free;

Conversely, the Test-and-Test-and-Set Spinlock (also known as spin on read) attempts to separate the write component from lock testing. We add an initial check to determine whether the lock is busy; this portion may be accomplished by accessing cached lock status, and does not cause any major issues with bus / interconnect traffic since it does not involve a write operation. Given a successful lock check (i.e., lock is free), we can then issue the test_and_set instruction.

1

2

3

def spinlock_lock(lock):

while((lock == busy) or (test_and_set(lock) == busy):

continue

This approach slightly increases latency and delay due to the extra test operation. On cache coherent architectures with write-update, this approach helps to reduce contention. However, this approach is not suitable for CC architectures with write-invalidate or NCC architectures.

Spinlock Delay mechanisms are an alternative which incorporates delay into the logic of lock acquisition. More specifically, we add a slight delay after lock release so that all tasks do not simultaneously attempt to acquire it. This approach reduces contention at the cost of delay. Delay may be implemented as static (fixed value) or dynamic (based on the perceived level of contention in the system). We can estimate this value by keeping track of failed test_and_set instructions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def spinlock_lock(lock):

while ((lock == busy) or (test_and_set(lock) == busy)) {

while (lock == busy) {

continue;

}

delay();

}

Finally, the Queuing Lock completely bypasses the issue of simultaneous test_and_set attempts by enforcing a queue structure. Once the lock frees, it signals the next task in the queue that the lock is available. This approach does have downsides - we must maintain $O(n)$ memory for the task queue, and have some read_and_increment atomic instruction to set queue status.

(all images obtained from Georgia Tech GIOS course materials)