GIOS M2: Processes

Module 2 of CS 6200 - Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems @ Georgia Tech.

What is a Process?

Overview

A process is an instance of an executing program. Processes are sometimes referred to as “tasks” or “jobs.” The concept of a process is one of the key abstractions an operating system supports.

Recall that the operating system is responsible for managing hardware on behalf of applications. When the application itself is not running, it is considered a static entity in memory. When the application is launched, it is loaded into memory and begins executing - the running application is considered a process. If the application is launched multiple times, each separate instance is considered its own process.

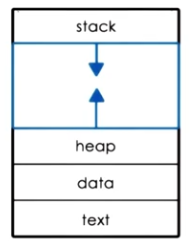

Any process encapsulates the entire state of a running application. State includes…

- Text and Data $\rightarrow$ static state provided at process initialization.

- Heap $\rightarrow$ dynamically-allocated memory assigned to the process.

- Stack $\rightarrow$ last-in-first-out (LIFO) queue structure which maintains state across function calls.

Each process has its own private virtual address space to index memory locations for the process. The virtual address space appears to the process as a continuous block of memory, but is actually an OS abstraction consisting of fragmented memory in the parent system - the OS provides page tables mapping virtual to physical addresses in memory (RAM).

\[\text{Virtual Address:~ 0x03c5} ~~ \xrightarrow{\text{Page Table}} ~~ \text{Physical Memory:~ 0x0f0f}\]Since main memory is limited, the OS typically assigns shared regions of physical memory to processes. When the memory is not currently required by the process, it can be swapped to disk to enable other processes to use this space. This is handled via Memory Management.

Process Management

In order for the operating system to manage processes (ex: pause + resume), it must have some general awareness of what the process is doing. Various values are maintained within a CPU register, which is a storage location on the CPU providing fast-access to values required for execution.

- Program Counter: process execution point in compiled program.

- Stack Pointer: current location in the process stack indicating corresponding state.

In general, the operating system maintains a Process Control Block (PCB) to track each process. The PCB is created and initialized on process initialization; certain fields are updated when the process state changes. The PCB includes data swapped to CPU registers (such as program counter and stack pointer for inactive processes), as well as other useful information (such as memory limits, open files, and CPU scheduling details).

Whenever a CPU changes execution from one process to another, the operating system must perform a Context Switch to swap the associated PCB data. Although multiple PCBs may be loaded into main memory, the CPU registers typically hold information specific to a single process. Therefore, context switching involves updating the CPU registers with data for the incoming process to execute. Context switching is relatively expensive for a few reasons:

- Direct Costs: number of CPU cycles for load + store of new data / instructions.

- Indirect Costs: cold cache and cache misses.

- CPUs have caches enabling additional storage of data for faster access to data compared to RAM. Note that a cache differs from a register in that the cache represents a larger “waiting room,” whereas the register represents a smaller “workspace.” The CPU typically has a cache hierarchy (L1, L2, L3), where higher priority caches provide faster access.

- Cold Cache: data in the cache is not relevant to the current process, and must be replaced with relevant data.

- Cache Miss: occurs when the CPU tries to read / write data expected to be in the cache (i.e., for a particular process), but this data is not present. Instead, the CPU must go to main memory to retrieve this data.

These costs imply we wish to minimize context switching whenever possible.

Process Lifecycle

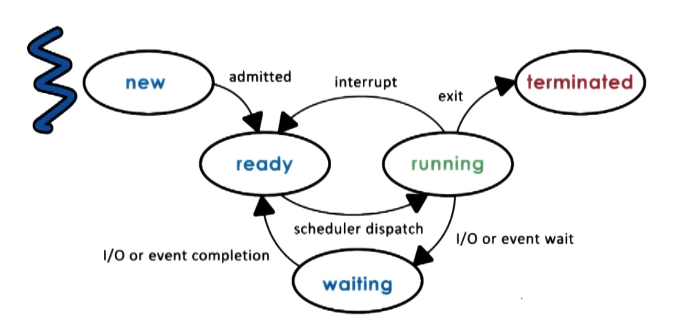

We have discussed processes in terms of two primary states:

- Running: process is currently executing on the CPU.

- Idle: process is waiting to execute on the CPU.

In reality, we have a more fine-grained definition of process state:

Creation

So how are processes created? Processes spawn other processes via a parent-child relationship; this implies that all processes share the same root. Most operating systems functions by first performing the boot process(es), then spawning a number of initial parent processes. The user may then create additional processes stemming from here.

The primary mechanisms for process creation are as follows:

fork: creates + initializes a child PCB, then copies info from the parent PCB into the child PCB. Parent and child continue execution at instruction immediately after fork point.EXEC: creates + initializes a child PCB, then loads a new program into the child PCB and start from the first instruction.

In practice, an operating system might call fork to create the initial process, then EXEC to update data in the PCB accordingly for the program of interest. On UNIX-based operating systems, init is the first process which starts after the system boots. Therefore, init is the root process relative to all user-initiated processes.

Scheduling

What happens when multiple ready processes are in the “ready queue”? The CPU Scheduler determines which of the currently ready processes will be dispatched to the CPU, and how long it should run for. The operating system therefore has a few key mechanisms pertaining to process scheduling:

preempt: interrupt current process and save its context / state.schedule: run CPU scheduler to select next process.dispatch: assign process to CPU and context switch as appropriate.

Ultimately, our CPU scheduler should 1) minimize the amount of time required to identify a process, and 2) manage processes in the most resource-efficient way. One important consideration is timeslice length - how much time should we allow a process to run uninterrupted on the CPU? Additionally, I/O operations have a key impact on scheduling - if a process has a long I/O duration, it may be more efficient for the CPU scheduler to select a new process + context switch as opposed to waiting for the I/O operation to complete.

Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

We have discussed processes as individual and isolated components managed by the operating system. However, are they actually as isolated as they seem? Processes can interact via Inter-Process Communication (IPC), which is an OS-provided mechanism enabling collaboration between multiple independent processes.

At the most fundamental level of an application, we typically require process interaction to accomplish a given functionality. For example, consider a web application which pulls from a backend database - the web server hosts and serves application content to a user (P1), while the database runs on the backend to store and query information (P2).

So how does IPC actually work? An operating system may provide many different IPC mechanisms to facilitate communication:

- Shared Memory: operating system establishes shared memory region, and maps it into the virtual address space for each process. Each process may then read / write messages in the shared region.

- Message Queue: processes similarly read from and write to a common channel, but this channel is located in kernel memory and managed directly by the operating system.

- Sockets: establish channel-based communication for both local and network sockets.

We will discuss these mechanisms more in future lessons.

(all images obtained from Georgia Tech GIOS course materials)