GIOS M3: Threads and Concurrency

Module 3 of CS 6200 - Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems @ Georgia Tech.

What are Threads?

Overview

A Thread is the smallest sequence of programming instructions that can be independently managed by a CPU scheduler. A thread is always a component of a process - put differently, we can only have a thread if we have a corresponding process. Processes may be single-threaded or multi-threaded.

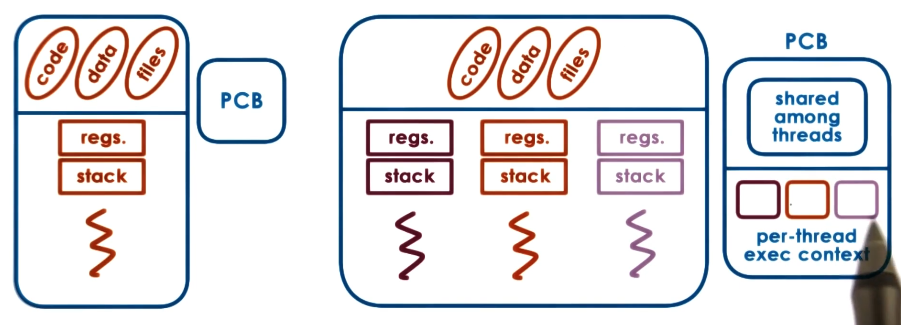

Recall that the process control block (PCB) stores all state associated with a process, where state can be broken down into process state (memory, files) and execution state (program counter, stack pointer). Threads of the same process share process state, but have independent execution state. The operating system’s representation of a PCB for a multi-threaded process is therefore more complex; it must maintain both the shared process-specific region and per-thread execution context (sometimes called the thread control block [TCB]).

Benefits

So what’s the point of using threads? Threads are useful for concurrency - instead of sequentially executing the instructions for an entire process on a single CPU core, we can break the process into multiple threads to execute in parallel on different cores. Parallelizing a process can often achieve substantial speedup!

We can design multi-threaded processes to serve different situations:

- Situation 1: process must be executed for multiple instances of an input matrix.

- Multi-Threaded Solution: each thread executes same code, but for different portion of matrix.

- Situation 2: process involves code portions which do not directly rely on one another.

- Multi-Threaded Solution: each thread is specialized to execute a particular section of the process. Specialization has particular benefits in terms of maintaining a hot cache.

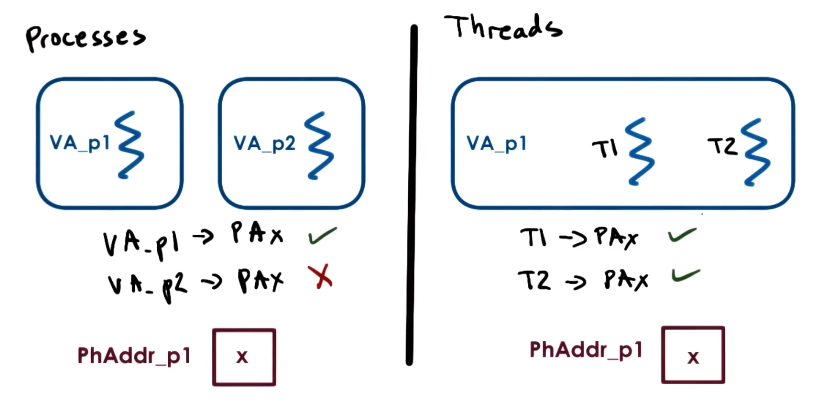

Okay, but wouldn’t a multi-process application accomplish the same outcome? Recall that each process has its own address space - multi-threading enables threads to share the address space of a single process, whereas a multi-process application would have several isolated address spaces. A multi-threaded application is therefore more memory efficient compared to its multi-process counterpart. Additionally, the shared address space implies less overhead for inter-thread communication (as compared to inter-process communication).

Single CPU

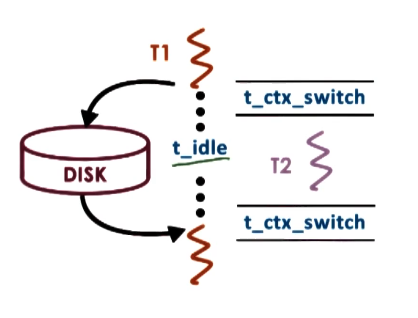

What if we only have access to a single CPU, or if the number of threads for a process is greater than the number of available CPUs? The CPU may still take advantage of idle time - for example, if thread T1 requires idle time for an I/O operation greater than the overhead of context switching to (and from) thread T2, it is more efficient for the CPU to execute T2 while waiting for T1’s I/O operation to complete.

But couldn’t the same be said for a multi-process scenario? Context switching between threads requires less overhead due to shared resources as compared to context switching between processes. Multi-threading is therefore useful for hiding additional latency incurred from idle times, even on a single CPU.

Thread Mechanisms

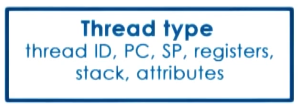

Now that we know what threads are, what does the operating system need to provide to support their usage? We should have some thread data structure to identify a thread and track its resource usage. We also need mechanisms to create, coordinate, and destroy threads.

Creation + Destruction

Threads may either be directly provided by the operating system, or via some system library which facilitates multi-threading. Similar to a process, each thread must have a data structure to both identify itself and store any necessary state-related data.

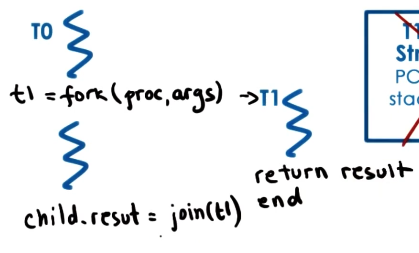

Threads may be created in a number of ways. In this lesson, we will follow the details proposed in An Introduction to Programming with Threads (Birrell, 1989). First, assume that each process begins with a single thread (by the definition of a process). We define fork(proc, args) to create a thread from an existing thread - the resulting thread begins execution at proc with the context of args available on its stack. Once the created thread has finished execution, the parent thread calls join(thread_id) to gather any results and deallocate memory corresponding to the finished thread.

Coordination

Threads access the same shared virtual address space (VA) - this means thread coordination should be particularly cognizant of potential issues resulting from concurrent read / write operations.

If two threads T1 and T2 both have access to the same physical memory location PA, certain race conditions can occur:

T1attempts to read the data stored atPAwhileT2is modifying.T1therefore reads garbage or logically-invalid results (depending on desired order of modification / read).T1andT2write to the same locationPAat the same time, resulting in one thread overwriting the efforts of the other.

To avoid these issues, multi-thread programs use Synchronization Methods to coordinate access to shared resources across multiple threads. More specifically, the concept of mutual exclusion guarantees that only a single thread has access to a shared resource / critical section of code at a time.

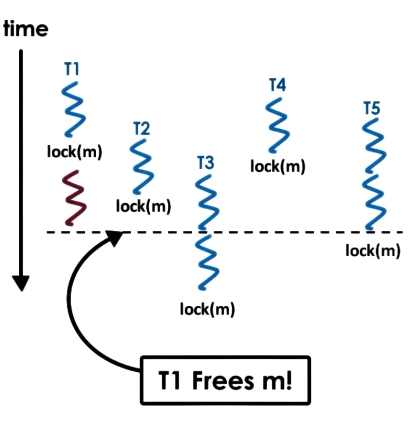

How do we implement mutual exclusion? A Mutex is a locking structure which must be acquired to access state / resources shared across multiple threads. When a given thread acquires the mutex corresponding to a particular shared resource, it has exclusive access to that resource. Other threads attempting to acquire the lock are blocked until the acquiring thread releases the lock. To visualize the locking construct, consider the following example: treads T1, T2, and T3 must each execute a critical section of code within A before proceeding to B, C, and D.

Within our program, we must explicitly lock the mutex before entering a critical section of code, and explicitly release it via some unlock method.

1

2

3

lock(m);

// critical / shared section

unlock(m);

If any thread attempts to lock the mutex while it is already acquired, they must wait for the owning thread to unlock the mutex before proceeding. If multiple threads are waiting, there is no guarantee which will successfully lock the mutex upon its release! Consider the following example - T2, T3, and T5 are each viable candidates for acquiring the mutex.

We may have the situation in which we only wish to execute code depending on some condition. For example, in a producer-consumer multi-threading framework, we may have a shared list that the consumer should clear whenever it becomes full. Condition Variables are used to signal to waiting threads that a condition has occurred, and it can therefore proceed. Any condition variable API typically implements the following structures / methods:

Condition cond: variable used to signal the condition has occurred.Wait(mutex, cond): automatically releases mutex, then reacquires oncecondis signaled.Signal(cond): notifies a single waiting thread that the condition had occurred.Broadcast(cond): notifies all waiting threads that the condition has occurred.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

// create threads

for (int i=0; i<10; i++) {

producers[i] = fork(safe_insert, NULL);

}

consumer = fork(print_and_clear, my_list);

// producer function: safe insert (not completely valid, but you get the idea)

void safe_insert() {

lock(m);

my_list.insert(my_thread_id);

if (my_list.is_full()) {

Signal(list_full);

}

unlock(m);

}

// consumer function

void print_and_clear() {

lock(m);

while (my_list.not_full()) {

Wait(m, list_full);

}

my_list.print_and_clear();

unlock(m);

}

Our current framework is suitable for writers, but this seems too restrictive in the case of readers. What if we’d like to have multiple readers access the shared resource simultaneously? We should define the following possible scenarios:

(read_counter == 0) & (write_counter == 0): any read thread(s) or single write thread may access resource.(read_counter > 0): only additional read threads should access resource.(write_counter == 1): no additional thread (read or write) should access resource.

We can introduce a level of indirection by applying the mutex to some resource_counter, and requiring each thread to proceed through the resource counter before accessing the shared section. For example…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Mutex counter_mutex;

Condition read_phase, write_phase;

int resource_counter = 0;

// READERS

lock(counter_mutex);

while (resource_counter == -1) {

Wait(counter_mutex, read_phase);

}

resource_counter++;

unlock(counter_mutex);

/* perform read operation */

lock(counter_mutex);

resource_counter--;

if (resource_counter == 0) {

Signal(write_phase);

}

unlock(counter_mutex);

// WRITER

lock(counter_mutex);

while (resource_counter != 0) {

Wait(counter_mutex, write_phase);

}

resource_counter = -1;

unlock(counter_mutex); // important for writer to release so readers can check!

/* perform write operation */

lock(counter_mutex);

resource_counter = 0;

Broadcast(read_phase);

Signal(write_phase);

unlock(counter_mutex);

Note that the critical section in this example is represented by the read / write operation… we are indirectly controlling access to this section by locking on resouce_counter proxy variable.

Common Pitfalls

Spurious Wake-Ups occur when our program signals to awake threads, but these threads may still have to wait for the mutex to release before proceeding. While this doesn’t cause any direct issues with the program, it may result in the awoken threads unnecessarily spinning on the CPU (and thus wasting cycles). To avoid spurious wake-ups, we should perform broadcast / signaling operations only after unlocking a mutex - this isn’t always possible depending on program’s logic.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

// writer with spurious wake-ups

lock(counter_mutex);

resource_counter = 0;

Broadcast(read_phase); // why signal if we still have the mutex?

Signal(write_phase);

unlock(counter_mutex);

// improved writer

lock(counter_mutex);

resource_counter = 0;

unlock(counter_mutex);

Broadcast(read_phase);

Signal(write_phase);

Alternatively, we could have the situation in which our multi-threaded implementation completely breaks under certain conditions. A Deadlock occurs when two or more competing threads are waiting on each other to complete, but neither can access the shared resource to do so. For example…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Mutex m1, m2;

// code for thread T1

lock(m1); // locks resource a

lock(m2); // locks resource b

t1_operation(a, b);

unlock(m1);

unlock(m2);

// code for thread T2

lock(m2);

lock(m1);

t2_operation(a, b);

unlock(m2);

unlock(m1);

The best method for avoiding deadlocks is to maintain a lock order such that threads should acquire the locks in a predefined sequence. Although this is trivial in the above example, this concept can be much more challenging to implement in complex programs involving many mutexes.

Multithreading Models + Architectures

Thread Level

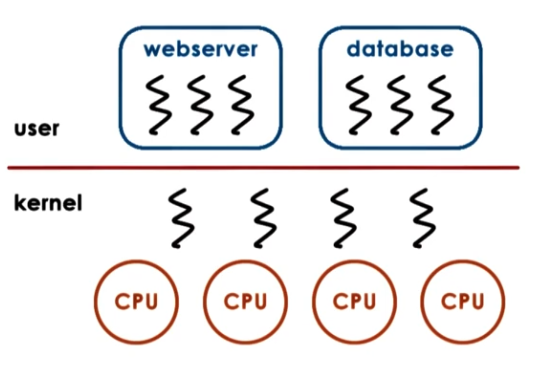

Threads can exist at both the kernel and user level. Kernel-level threads imply that the operating system itself is multi-threaded; the OS scheduler is therefore responsible for mapping these threads onto underlying CPUs for execution. Some kernel-level threads may exist to support user processes, and others may be dedicated to certain OS-level services (ex: daemon).

User-level threads must first associate with a kernel-level thread - then, the OS scheduler will map the kernel thread onto a CPU for execution.

Models

A Multi-threading Model describes a systematic policy for mapping user-level threads to kernel-level threads. There are many candidate models:

- One-to-One: each user-level thread is associated with a single kernel-level thread.

- Pro: OS has direct insight into application structure + understands synchronization / blocking logic.

- Con: must go through the OS for all operations; expensive to cross user-kernel boundary. Additionally, OS may have limits on policies for multi-threading.

- Many-to-One: all user-level threads are mapped to a single kernel-level thread. This implies a user-level library is responsible for multithreading synchronization.

- Pro: completely portable; multithreading does not depend on OS policies.

- Con: OS has no insight into application, and may block entire process if one user-level thread blocks on I/O.

- Many-to-Many: combination of both methods.

- Pro: best of both worlds!

- Con: requires additional coordination between user- and kernel-level thread managers.

Architecture

Since we implement multi-threading as part of our program, we can utilize many different Multi-threading Architectures to design how work is distributed across threads.

- Boss-Workers Pattern: single boss thread delegates tasks to each worker thread. Each worker is responsible for performing entire task before terminating.

- System throughput is limited by boss efficiency.

- Boss may assign work by directly signaling a specific worker, or pulling from a queue of workers. Workers may be specialized to perform certain tasks.

- Initialize by creating pre-specified pool of workers, then dynamically increase pool size depending on needs at execution time.

- Pipeline Pattern: overall process is divided into subtasks, and each thread is assigned a subtask in the system. This is particularly useful for tasks which much be repeated for different inputs (ex: processing an online order).

- System throughput is limited by the most expensive component of the pipeline. User can improve efficiency by assigning multiple threads to a single expensive component.

- Layered Pattern: overall process is divided into layers, where each layer is a related group of subtasks. Thread pools assigned to each layer.

(all images obtained from Georgia Tech GIOS course materials)