GIOS M5: Thread Design

Module 5 of CS 6200 - Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems @ Georgia Tech.

Thread Review

Overview

Recall that a thread is the smallest sequence of instructions (e.g., compiled code) that can be scheduled for execution on the CPU. Threads are organized as components of processes, where a process is a running instance of a program. By default, processes are single-threaded; designing a multi-threaded program enables parallel execution, which can drastically improve the performance (e.g., execution time) relative to the single-threaded counterpart.

Level

User-level threads are threads implemented in the user space. These threads are typically created by the user or user-level applications. In contrast, kernel-level threads are threads existing in the kernel space managed by the operating system.

User-level threads are provided by user-level libraries; the library must support thread data structures and mechanisms (e.g., scheduling, synchronization, etc.). For kernel-level threads, these functionalities are provided by the OS.

State

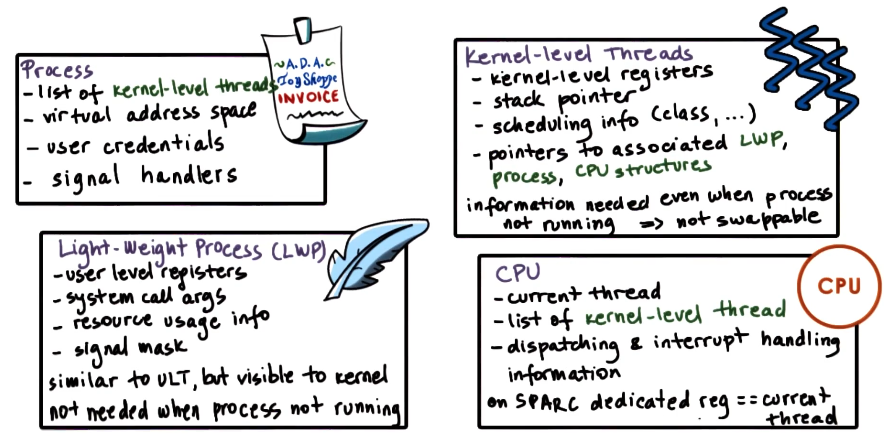

So what data structures do we need to support a user-level thread? The thread library maintains some thread control block (TCB) encapsulating thread state (UL thread ID, UL registers, thread stack, etc.). The operating system defines a process control block (PCB) for the thread’s parent process - importantly, this defines the address space for threads of the process. Finally, since user-level threads are mapped onto kernel-level threads before execution, the operating system must provide kernel-level thread structures + state (stack, registers) for support.

The PCB is distinguished into two components:

- Hard Process State: represents the state shared across all threads of a process (ex: virtual address space).

- Light Process State: state relevant to only a subset of user-level threads currently associated with a particular kernel-level thread (ex: signal mask, sys call arguments).

See below for a more detailed overview of thread-related structures maintained for a sample operating system (Solaris 2.0).

Management

An Example

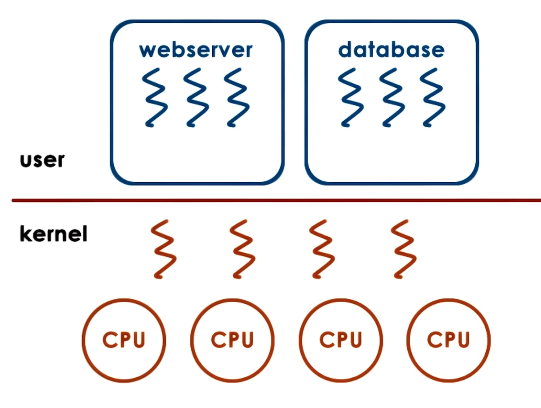

Given threads existing at the user and kernel levels, what are the basic interaction mechanisms? For this discussion, assume that “multi-threading” refers to a user-designed process consisting of multiple user-level threads.

When a multi-threaded process starts, the operating system provides it with some default number of kernel-level threads. The process may request additional kernel-level threads via system calls. User-level threads are mapped to kernel-level threads, and kernel-level threads are scheduled onto the CPU by the operating system.

Consider the case where the kernel-level threads now block due to some I/O operation. Even if user-level threads are waiting, the user-level library cannot see that the kernel-level threads have blocked - had the user-level library known this information, it could have requested additional kernel-level threads to continue maximizing concurrency.

Visibility and Design

We’ve emphasized that the kernel and user-level library have different levels of visibility when it comes to thread interactions. More specifically…

- Kernel: can see kernel-level threads, CPUs, and kernel-level thread scheduler.

- User-Level Library: can see user-level threads and available kernel-level threads.

Notification signals are the primary solution for any discrepancies in visibility. In the previous example, the OS may send a signal to the user-level library indicating that a kernel-level thread has blocked, and provide it with a new kernel-level thread to continue execution.

Destruction

Once a thread has finished executing, its memory should be deallocated to “clean up” and free system resources. However, what if we’re just going to create another thread shortly anyway? Instead of wasting time + resources initializing a completely new thread, we can reuse the thread-to-be-destroyed.

In practice, this is accomplished via a death row of threads. When a thread exits, it is marked for destruction and placed on “death row.” A reaper thread periodically clears out this list by destroying each thread. If a request for a thread comes in before the list is cleared, thread structures may be reused for the requested thread to enhance system performance.

Interrupts and Signals

What’s the Difference?

Interrupts are notifications which indicate some event external to the CPU has occurred. Interrupts can be generated by components such as I/O devices (ex: network packet has arrived), timers, etc. Interrupts appear asynchronously; this implies they are not in direct response to some event occurring on the CPU.

Signals are notifications triggered by the CPU and any software running on it. Unlike hardware interrupts, signals can appear either synchronously or asynchronously.

Both interrupts and signals have a unique identifier (depending on hardware platform / OS). Additionally, both can be masked and disabled / suspended on a per-process basis. Masking is accomplished using a sequence of bits, where each bit corresponds to an interrupt / signal and indicates whether or not the interrupt / signal should be ignored.

Assuming no masking, the interrupt / signal will trigger its corresponding event handler, which is a sequence of instructions reserved for dealing with the particular event type.

- Interrupt Handler: set for entire system by OS.

- Signal Handler: set on per-process basis by process.

Interrupt Handling

Interrupt handling works as follows. The physical device sends an interrupted (identified via MSI number) to the CPU. The CPU then references a lookup table of supported interrupt types to handlers. Given a match, the CPU program counter is set to the start address of the appropriate handler, and the CPU begins execution. Therefore, the physical platform / device determines when to issue an interrupt, and the OS determines how to handle interrupts via its interrupt-handler lookup table.

Signal Handling

Since they are not generated by an external entity, signals work a bit differently than interrupts. Upon some signal-inducing event, the OS generates a signal which is sent to the applicable thread. The thread may then reference some user-level library or process-specific table to map the signal to its corresponding event hander.

Here’s an example of a signal in Linux:

- Thread

T0attempts to access illegal memory. - OS issues

SIGSEGVsignal, sending it back to the thread. - Thread

T0handles theSIGSEGVsignal as defined by the process.

The OS has default handlers/actions for signals - these include actions such as terminate, ignore, stop, or core dump. The process can override these default actions by implementing its own handler. This can be done via integration with a user-level library, or by explicitly coding signal handler(s) within the process.

Types of Signals

There are two primary types of signals:

- One-Shot Signals: if multiple instances of the same signal occur, the signal handler is executed only once. Handler must explicitly be re-enabled after each use.

- Real-Time Signals: handler is called once for each signal.

A dictionary of signals specific to Linux (such as SIGINT and SIGKILL) can be found here.

Applications to Linux

Processes in Linux

Like all other operation systems, Linux has a specific abstraction to represent processes. Linux’s primary abstraction to represent an execution context is the task. A task is essentially the execution context of a kernel-level thread; a single-threaded process will have one task, and a multi-threaded process will have many tasks.

Any task contains the following information:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

struct task_struct {

pid_t pid; // every task has a unique pid (process id)

pid_t tgid; // tgid designates "thread group" id

int priority;

volatile long state;

struct mm_struct *mm;

struct files_struct *files;

struct list_head tasks;

int on_cpu;

cpumask_t cpus_allowed;

}

Unlike the framework previously outlined, Linux does not use process control blocks. Instead, it encapsulates process information via pointers within the task abstraction.

Threads in Linux

The current implementation of Linux threads is called Native POSIX Threads Library (NPTL). This implementation is a one-to-one model in which one user-level thread is mapped to one kernel-level thread. This enables the kernel to better view + manage user-level threads.

(all images obtained from Georgia Tech GIOS course materials)