GIOS M7: Scheduling

Module 7 of CS 6200 - Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems @ Georgia Tech.

What is Scheduling?

Overview

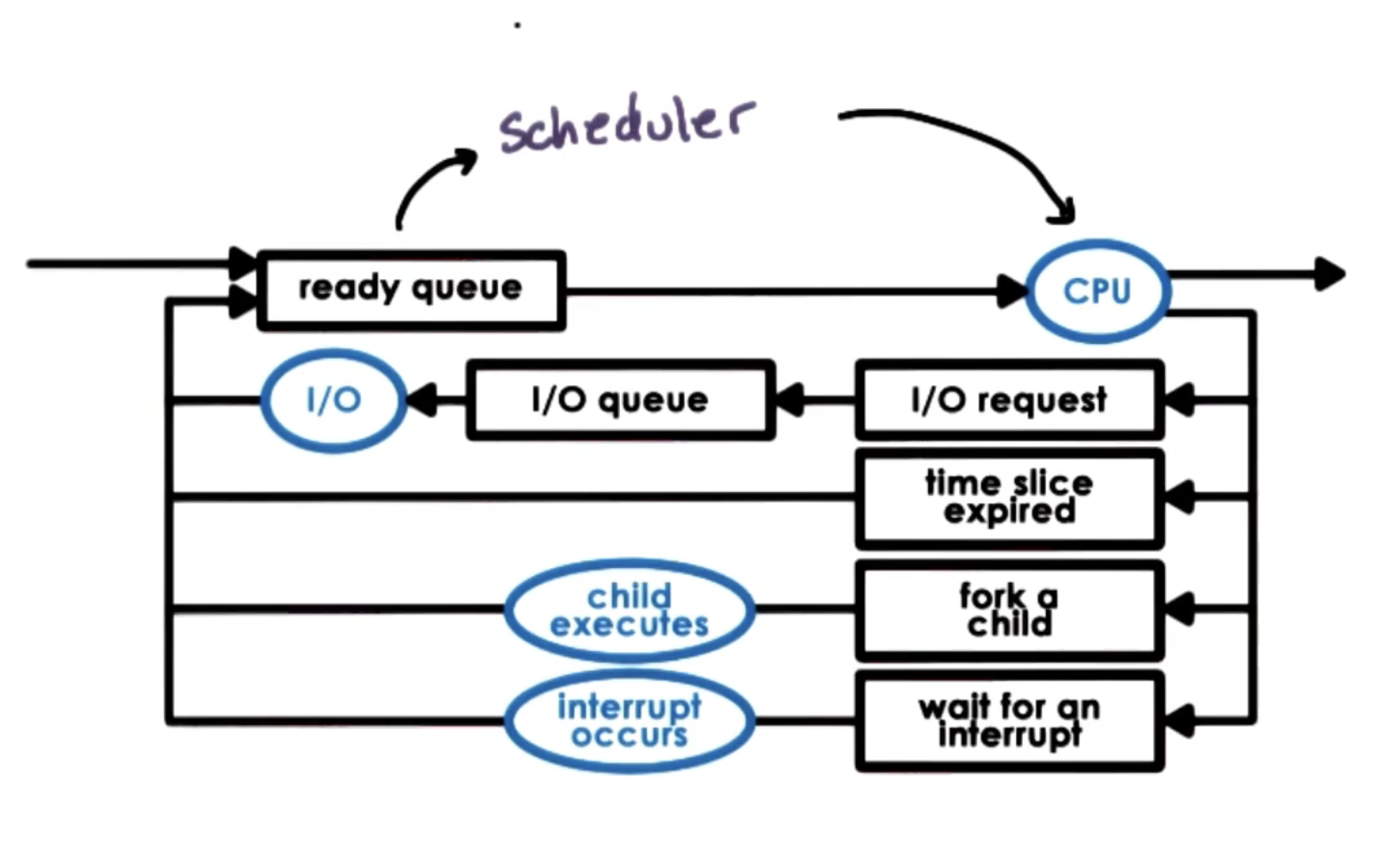

In the context of operating systems, the Scheduler is responsible for managing task assignment to the CPU, where a task may refer to a process or a thread. The OS scheduler is responsible for managing how and when tasks are dispatched to available CPU(s). The scheduling policy specifies these rules, and is typically unique to a given scheduler.

Consider the following simple scheduling policies:

- First-In First-Out (FIFO): tasks are scheduled in the order they appear.

- Shortest Job First (SJF): OS estimates task length, then prioritizes threads with shorter execution times.

- Round Robin: assign a period of time for uninterrupted task execution (called a timeslice), then cycle through tasks applying this time (and removing when it expires).

Put more concretely, the scheduler is responsible for selecting a task from the ready queue to dispatch onto an available queue. See below for an example implementation of the round robin approach.

Scheduling Policies

Let’s take a closer look at the policies defined earlier. Scheduling policies can be broadly grouped as follows:

- Run-to-Completion Scheduling: each scheduled task runs on the CPU until it has completely finished. Tasks are not interrupted based on time constraints.

- Preemptive Scheduling: alternative framework where tasks may be interrupted (typically based on timeslices).

- Preempt (in the context of operating systems): involuntary interruption of a running task by the scheduler to reclaim the CPU.

FCFS is classic example of run-to-completion scheduling. SJF may be implemented according to run-to-completion or preemptive scheduling. In the latter case, any shorter arriving task may take priority over the currently-executing task. We can also introduce task priority level to further control preemption logic.

Round Robin Scheduling is a form of preemptive scheduling which relies on timeslices to define the maximum amount of time a task should run uninterrupted on the CPU. Once a task’s timeslice expires, it is interrupted and another task is dispatched onto the CPU. Similar to SJF, round robin scheduling can be implemented with or without priority level.

More on Timeslicing

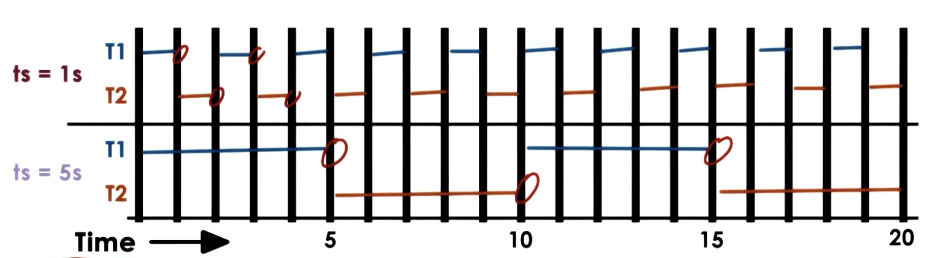

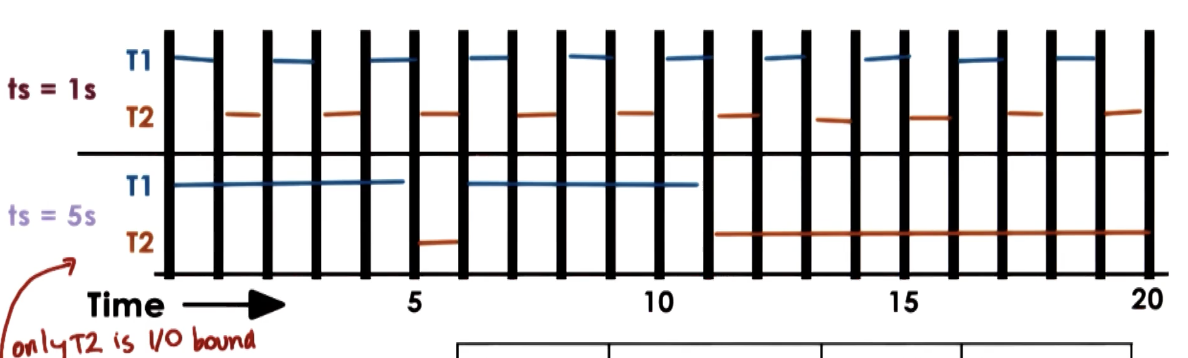

How should we determine the optimal timeslice length? The solution depends on whether we primarily have CPU-bound tasks vs. I/O-bound tasks.

- CPU-bound tasks: longer timeslice is preferred to outweigh context switching overhead. Longer timeslices correspond to greater throughput, and lesser average completion time.

- I/O-bound tasks: in the case of only I/O-bound tasks, the timeslice should be large enough so that I/O tasks yield (block) voluntarily. In the case of a single I/O bound task (

T2), shorter timeslices result in better performance.

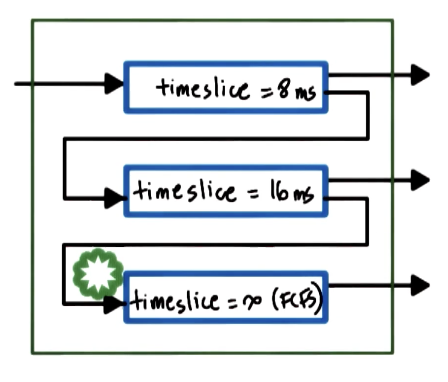

Furthermore, we can dynamically define timeslice values via some multi-level feedback queue, where each level of the queue corresponds to a particular timeslice value. If a task hits the timeslice limit without blocking, we bump it down to the next (longer) timeslice tier for its next iteration. Similarly, if the task does not exhaust its timeslice, it will be associated with a shorter timeslice tier in the next iteration.

Schedulers in Practice

Linux

The Linux O(1) Scheduler is a preemptive, priority-based scheduler which selects tasks from the run queue in constant time, regardless of the number of tasks in the queue. It uses timeslice values to regulate task execution time on the CPU, and adjusts timeslice values via feedback mechanisms.

- Timeslice Value: small for low priority, large for high priority.

- Feedback: boosts priority for longer sleep (I/O tasks), reduces priority for shorter sleep.

The O(1) scheduler maintains two lists of tasks: an active list holding tasks in the ready queue, and an expired list of tasks which have already used their timeslice. Once the active list is empty, the pointers for the two lists are swapped.

There are certain limitations to the O(1) scheduler. First, we must wait for the entire active list to clear before repeating task execution. This impacts the performance of interactive tasks (lots of jitter). Additionally, the O(1) schedule does not make any guarantees with regards to fairness.

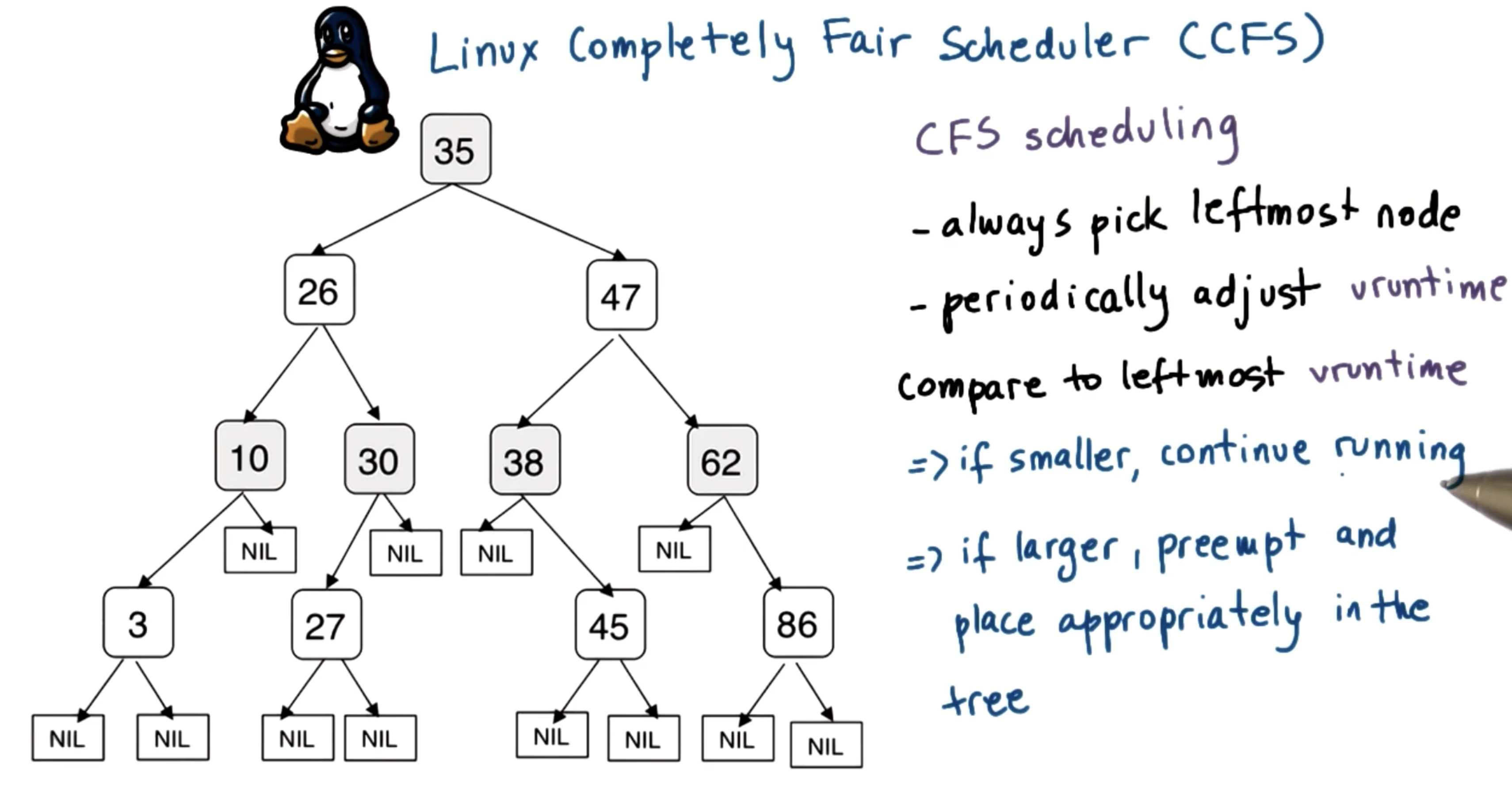

To resolve these issues, the Completely Fair Scheduler (CFS) was introduced. CFS is currently the default scheduler used in Linux. CFS uses a red-black tree as its runqueue structure; at its core, a red-black tree is a binary search tree with self-balancing after each node addition. CFS adds tasks to the tree based on virtual runtime, and always selects the leftmost node (least virtual runtime) at each scheduling step.

CFS does not represent virtual runtime as 1:1 with real execution time. Virtual runtime accumulates at a faster rate for low-priority tasks compared to high-priority tasks.

Multi-Processors

How does scheduling work on multi-CPU systems? First, let’s more concretely define our system. A Shared Memory Multiprocessor (SMP) is a multi-CPU system which shares a main memory (RAM) unit. Each CPU typically has its own cache, and a given CPU may have multiple cores.

The main additional consideration as part of a multi-CPU system is cache affinity. Our scheduler should dispatch to maximize “hot caches” by keeping tasks on the same CPU as often as possible. Modern schedulers such as CFS handle scheduling on SMPs by maintaining per-CPU runqueues, with load balancing to intentionally break cache affinity as necessary to better distribute the workload.

Hyperthreading Platforms

Hyperthreading refers to multiple hardware-supported execution contexts within a single CPU, but with VERY fast context switching. This approach enables instructions from multiple threads to execute simultaneously on shared functional units, effectively hiding memory latency. Hyperthreading is also known as Chip Multithreading (CMT) or Simultaneous Multithreading (SMT). Each hardware context appears to the operating system as a separate virtual CPU.

(all images obtained from Georgia Tech GIOS course materials)