GIOS M8: Memory Management

Module 8 of CS 6200 - Graduate Introduction to Operating Systems @ Georgia Tech.

Overview

Memory Management is the process of controlling and coordinating a computer’s main memory (RAM), with specific regards to allocation / deallocation and use optimization.

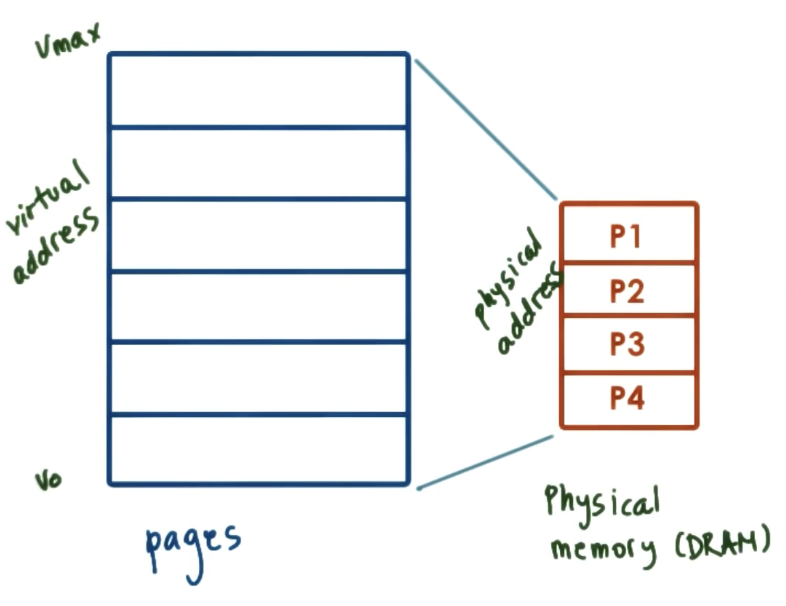

Recall that each process has its own virtual address space, which maps memory pages (virtual memory) to page frames (physical memory). Alternatively, an OS might support segment-based memory management, where segments are more flexibly-defined regions of virtual memory.

Memory Structures

Hardware

What sort of hardware support does a computing system provide in terms of memory management? The Memory Management Unit (MMU) is a physical subdivision of the CPU, and has a few key responsibilities:

- Performs translation of virtual to physical addresses by navigating page table (stored in main memory).

- Report faults - attempt to access illegal region of memory (relative to current process).

Other hardware components provide support in indirect ways:

- CPU Registers: store pointers to page table (for page-based memory system), or segment parameters such as base / limit segment size + number of segments (for segment-based memory system).

- MMU Cache: maintains translation lookaside buffer (TLB) to keep valid VA-PA translations for fast-access.

Page Tables

Definition

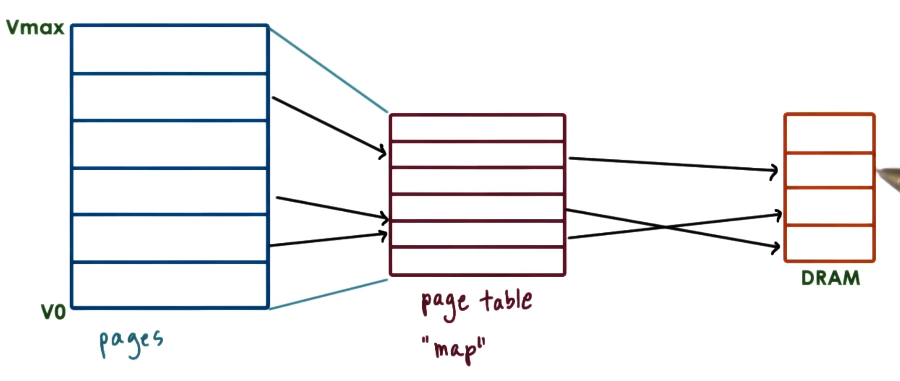

Pages (as opposed to segments) are the more popular method for memory management. A Page Table defines the mapping between any virtual page and a page frame in DRAM. Page tables are specific to processes + stored in RAM - the process control block (PCB) contains a pointer to the relevant page table.

Pages have expected size (specified by page category), which facilitates an easier virtual-to-physical translation process. For example, pages and page frames may be uniquely identified by their starting memory address, as opposed to keeping track of the start and end addresses. This implies that the contents of an individual page frame (in physical memory) must be contiguous.

Use within Translation

How does the MMU perform translation between a virtual page and physical page frame?

- MMU is queried with a virtual address of interest.

- MMU splits virtual address into…

- Virtual Page Number (VPN): index in page table corresponding to virtual page.

- Offset: number of positions from the starting memory address of virtual page.

- MMU indexes into page table using VPN. VPN is associated with Physical Frame Number (PFN), which is the starting memory address corresponding to the physical page frame.

- MMU concatenates offset with PFN to yield final physical address of interest.

Managing Page Table Entries

What happens when a process requests memory via allocation (such as with malloc in C or new in C++)?

- First, the allocation is performed in virtual memory. In practice, this means we assign the starting virtual memory address of the allocated virtual memory to a pointer.

1

2

int size = 10;

int* arr = new int[size];

- Although we’ve established a virtual page, the OS does not define a mapping between this virtual page and a physical page frame until the virtual page is used.

- When the process attempts to access this memory for the first time, the OS will select a page frame to map to, and define the appropriate mapping in the process’ page table.

1

arr[5] = 3;

- If the process does not utilize this memory for some time, the corresponding physical page frame may be swapped from RAM to disk to free up main memory for other processes.

- When the process deallocates this memory, the OS removes the associated entry from the page table and marks the physical page frame as free for use. This might not happen immediately depending on current system memory demands.

1

delete[] arr;

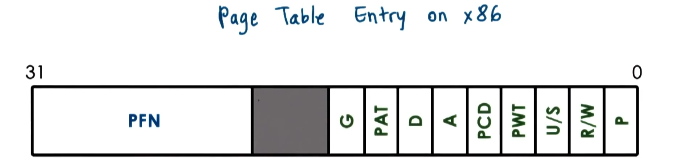

Every page table entry is uniquely identified by VPN, and typically contains the following information:

- PFN: physical page frame associated with the virtual page.

- Flags:

- Present: is the page frame in main memory? (as opposed to swapped to disk)

- Dirty: has the page / page frame been written to?.

- Accessed: has the page / page frame been accessed?

- R/W: does the process have read permissions? write permissions?

- U/S: is the page frame accessible from user mode, or supervisor (privileged) mode only?

The MMU uses page table entries to perform address translation, and also establish validity of access. If the MMU determines that the requesting process cannot access its requested memory location, it will generate a page fault. This involves passing control to the OS to call the appropriate page fault handler. For example…

- If the page fault is a result of the page not being present in main memory, the OS will swap the required page frame from disk to RAM.

- If the requesting process does not have permission to access the requested page frame, the OS will issue a page fault signal (e.g.,

SIGSEGVon Linux).

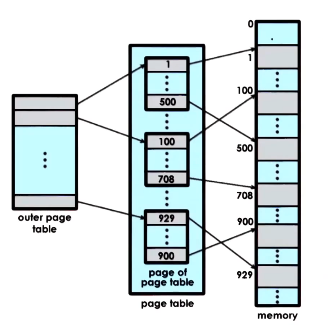

Multi-Level Page Tables

Page tables aren’t typically defined in a flat manner. Instead, we use a hierarchical structure to enable more efficient indexing and memory usage. For example, a two-layer page table dedicates its first layer to indexing pages of page tables, and its second level to indexing page entries (mapping virtual pages to page frames).

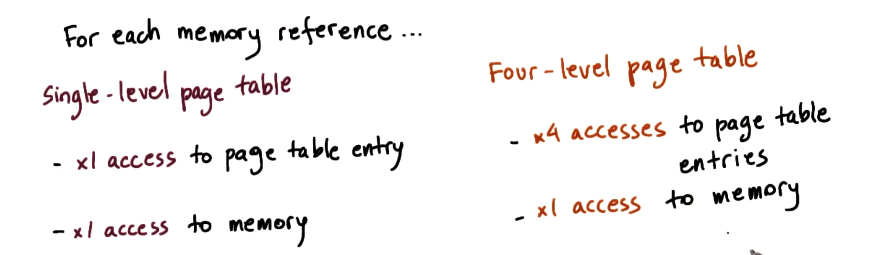

We can extend this principle to apply to n-level page tables. The primary downside of using deeper multi-level page tables is the amount of memory accesses (and corresponding overhead) associated with a single translation.

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

The translation lookaside buffer (TLB) is used to increase translation speed, especially in the context of multi-level page tables. Without the TLB, we have overhead proportional to page table depth:

The TLB is a cache within the MMU which maintains valid virtual-to-physical address mappings. Even a small number of cached translations can result in high TLB hit rate, and thus solid performance gains. Obviously, we should not maintain all possible mappings in the TLB due to 1) infeasibility in terms of cache size, and 2) degrading our TLB to simply be a single-level page table!

Mechanisms for Memory Management

Memory Allocation

Memory Allocation refers to the process of reserving main memory (RAM) for a virtual address. In practice, this means defining a valid mapping between the requested virtual page and a free-for-use page frame. The memory allocator determines virtual-to-physical address mapping as part of memory allocation.

Kernel-level allocators allocate memory for the kernel - this is typically done for kernel state and kernel process management. These allocators are also responsible for keeping track of free physical memory in the system.

User-level allocators allocate memory for dynamic process state (ex: heap region of a program’s memory). This is accomplished via the malloc / free methods in C, and the new / delete methods in C++.

Challenges

One common challenge of memory allocation is external fragmentation, which refers to the case where multiple interleafed malloc and free operations result in fragmented physical memory. External fragmentation can occur in the context of both virtual and physical memory - consider the following examples.

- Virtual Memory Fragmentation: new allocation request requires memory of certain size (ex: four pages). Virtual memory may have this space available, but not in a contiguous format.

- Physical Memory Fragmentation: kernel might require contiguous physical memory in the case where a virtual address abstraction is not utilized.

In either case, allocation algorithms (implemented at the allocator level) are responsible for limiting instances of external fragmentation, as well as reorganizing free memory regions into contiguous blocks at various intervals.

Linux Allocators

The Linux kernel relies on two basic allocation algorithms:

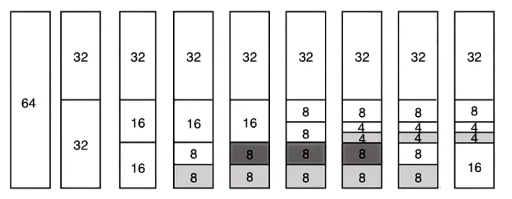

- Buddy Allocator: given a $2^x$ region of free memory, the buddy allocator subdivides this area into smaller chunks (also a power of 2). It will continue subdividing until finding the smallest chunk (with size of power 2) to satisfy the request.

- By subdividing memory, the buddy allocator can check “buddies” (adjacent subdivided regions) on

freeoperations and determine if aggregation of free memory is possible. Memory sizes of $2^{x}$ ensure that buddy addresses differ by only a single bit. - For example, consider the following sequence of requests:

malloc(8); malloc(8); malloc(4); free(8);

- By subdividing memory, the buddy allocator can check “buddies” (adjacent subdivided regions) on

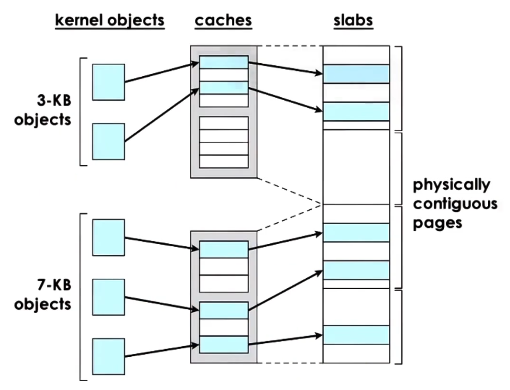

- Slab Allocator: builds custom caches for particular object types (where the cache contains pointers to free memory of template size). Upon request for a particular object, uses the cache to quickly map to an appropriate region of contiguous memory.

Linux uses a combination of buddy and slab allocators, since the use of buddy alone would result in substantial internal memory fragmentation (e.g., in the case where requested memory size is nowhere close to a power of 2).

Demand Paging + Page Replacement

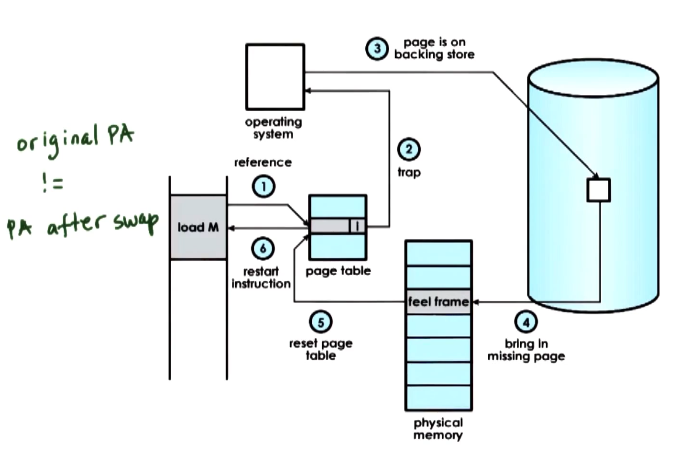

Physical main memory (RAM) is much smaller than virtual memory across all processes. To support this scenario, the OS does not keep all virtual memory pages in RAM at any given time. Instead, the page frame corresponding to a particular virtual page can be saved / restored relative to secondary storage locations (e.g., disk). Demand Paging refers to swapping pages between main memory and a swap partition as needed.

For example, consider the case where a process attempts to access memory that is currently “paged out” onto disk. The OS must return the missing page back to physical memory, then restart the access instruction.

Demand paging typically defines a different page address (depending on the current state of free main memory) for the same page when swapped back into RAM, relative to its original page address when the memory was first allocated. If the page should have constant page address / be present in RAM at all times, we must specify that the page should be pinned - this simply means swapping for the page is disabled. This is useful when the CPU is interacting with devices that directly interact with RAM.

Our current framework still leaves some uncertainties:

- When should pages be swapped out?

- The OS determines if memory usage is above a particular threshold, or CPU usage is below a certain threshold.

- If either threshold is met, the OS runs a “page-out” daemon to identify pages which should be swapped out of main memory.

- Which pages should be swapped out?

- The OS uses some policy to predict whether or not pages will not be required for use in the near future. One example policy is Least Recently Used (LRU).

- Other candidates are pages which do not need to be actively written out to disk. For example, if the dirty bit for a particular page frame is 0, this means we can use the version of the page frame already stored on disk.

(all images obtained from Georgia Tech GIOS course materials)